Ubaji Isiaka Abubakar Eazy

Very few understand the power in words. Not all know of how a few damaging words could ignite a conflagration or spark off a revolution. Not all know, but oppressors know this and they fear the man of words. They fear the man who refuses to tow the path of silence or become a parrot that sings for rewards of peanuts. This explains why writers are often the targets of repressive regimes. Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac popularly known as Gaarriye is one of such rare men who sees silence as a blemish and refuses to indulge in it despite intimidations from a brutal government regime. Indeed, the voice of a poet is golden, and it is a voice that calls for caution even as it appeals to the ears of all.

Today, I hold in my hands a translated version of Gaarriye’s poems and his biography entitled Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac “Gaarriye:” Biography and Poems (translated by W N Herbert et al, and edited by Jama Musse Jama) and I am compelled to write this review after meeting the words of this great poet, albeit in a translated format.

Gaarriye’s poems in this collection are either political or about love. His love poems are elegant, and they reveal a lot about the Somali culture and the topography of the Somali society. His political poems, on the other hand, are combatant and come packed with justifiable anger for Gaarriye is the soldier poet whose only weapon is a pen that shoots words. This is why he says in the first poem in this collection thus:

More importantly, Gaarriye’s political poems also exhibit the poet’s defiance to those in positions of power. Shall we now enter into the realm of the poem? Let’s see them then.

‘Mandela’ is the first poem you encounter in the collection, and as the name suggests, it is about the South African freedom fighter who demolished the wall of apartheid, Nelson Mandela. The poem is a voice in support of the cause of democracy and freedom which Mandela represents and has come to symbolize, not only in South Africa, but in the world as a whole. Gaarriye recognises the racial dichotomy in the South African society with the Whites being the oppressors and Blacks being the oppressed. He emphasises that Mandela cannot win a case heavily tilted against him, certainly not when the laws he will be judged with emanates from the white oppressors, not when:

The Oppressor comes into court.

He is the Prosecutor,

He is the Judge and Jury;

There is no ‘win or lose’ –

The case is cut and dried.

The Defendant stands alone.

The Prosecutor calls

Himself as Witness – yes,

The Judge upholds the law

That he himself created:

It changes as he chooses.

The Jury only knows

One word – the word is ‘Guilty’.

Indeed, ‘Guilty’ it is for when has it ever been heard that the rat is judged innocent in court owned and controlled by a clowder? Gaarriye hopes that his poem will continue to propagate Mandela ideology of a democratic and free society even if Mandela is gagged by incarceration.

However, we must point out that while the poem hopes to propel’s Mandela’s ideology, it is even more an attack on the repressive military regime of the then Somalia dictator, Siad Barre. It is at this point that we begin to see Gaarriye’s shrewdness as a poet.

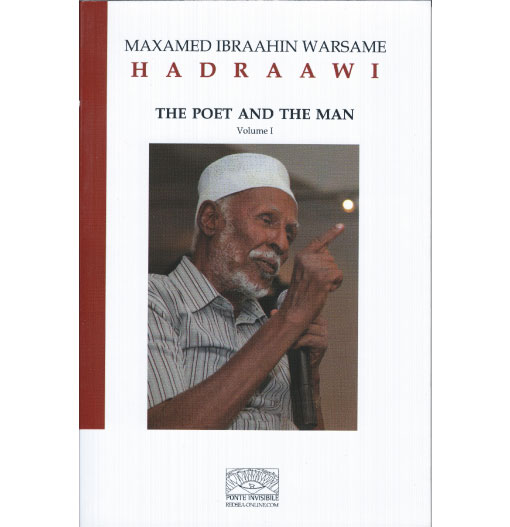

You see, while Black Africans were struggling against the system of racial segregation infamously known as Apartheid in South Africa, Somalia was also contending against the oppressive regime of Siad Barre. It was an autocratic system of government that antagonises democratic and libertarian ideals similar to what Mandela and his compeers were up against in South Africa, the only difference being perhaps that the case of Somalia was not racially influenced. Nonetheless, it was still the same case of oppressors and the oppressed; this is how Gaarriye wants us to see things. Mandela’s plight in South Africa therefore becomes a facade for throwing concealed punches at the poet’s home government and a rallying cry to awaken the oppressed. Evidence of this lies in the last three stanzas of the poem where the poet calls on fellow griots (Abu Hadra and Hadraawi) and pleads that they listen to him, he intimates that the poem infers more than its surface meaning when he mentions that it is only by listening that they can understand ‘the blade’ hidden deep within the poem. He also calls the poem ‘a mirror’ when he calls on Hadraawi to listen to him thereby suggesting the similarity of the problem in South Africa to that of Somalia:

So listen, Abu Hadra!

If you will listen, others

Will listen too, will hear

The words as if Mandela

Was calling them to arms.

They’ll grasp the blade that’s hidden

Deep inside this poem;

They’ll show the Judge and Jury

The cutting-edge of freedom;

They’ll show the Prosecutor

The blade that lasts forever;

They’ll never bow their heads

Or walk in chains and fetters.

This poem is a mirror

I’ve made for us, Hadraawi,

A mirror we can hold up

To show the ignoramus

The depth of self-deception

That lies in his reflection;

To show the Judge and Jury

How the wide world sees them;

To show the man who takes

Pleasure in pain the guern

Of glee that warps his smile.

Hadraawi, read this poem

To anyone who’ll listen.

Help them to find the voice

I’ve given to Mandela.

And tell them this: our purpose

Is peace; our password ‘Freedom’;

Our aim, equality;

Our way the way of light.

However, poets are not just soldiers of words, they are also the vanguards of society; they are Tiresias guiding the people in the way they should go, they are prophets who must choose never to compromise their truth and sense of justice for mendacity and injustice. And it is this that we see in another of Gaarriye’s poems titled “Seer”. In this poem, Gaarriye recognises the important role of poets and poetry in the society and urges poet to never compromise. This poem is in two parts and written using a flashback technique whereby Gaarriye recalls the words of his female guardian; Biliso; to him. In the first part, he (Gaarriye) says she taught him that poetry is ‘the best words for the best thoughts’ and advised him to always stick with the truth no matter what happens:

Justice is your only compost,

life itself is what you hoe:

just squeeze truth from what happens

and in its own time it will sprout.

She also tells him that poetry is not for charlatans whose stock in trade is lies because they want to cavort with the oppressors. She warns him that the art of poetry must be kept pure and not be betrayed or cheapened by being sold for a price. She says poetry:

guides you like a conch shell horn,

the call of the large camel bell;

it is the words’ own bugle.

It is the finest matting, woven for a bride,

the one the song calls ‘Refuser of poor suitors’.

It’s not sold for coppers,

it’s not for praising the powerful;

to put a price on it, any price,

cheapens it and is forbidden.

‘It’s riding bareback on an unbroken horse –

you don’t hobble its heels.

Those who fear for their hides

and won’t ride without a saddle,

those lacking in the craft, can’t get near this:

lies have nothing to do with it.

Poetry is a woman you do not betray,

to abuse her beauty is a sin.’

By recalling the words of his aunt and guardian, Gaarriye hopes to leave a great impression on the minds of fellow poets whose major preoccupation includes subduing the truth while singing eulogies of the political class. He warns them not to swap the truth in their poem for a pocket lift.

It is the voice of Biliso we meet still in the second part of the poem at hand (‘Seer’). And this time, she tells of the emotional fulfillment that the well written poem endows both the poet and its readers.

‘Self-Misunderstood’ is written in a form of poetic soliloquy whereby we are made to listen in on the poet’s thoughts as he attempts to understand his second self. This second self can be described as his conscience and we hear the poet speak to this second self. Both aspect of the same person seem to be in constant conflict for Gaarriye makes us to understand in this poem that there seem to be more than one Gaarriye occupying one body and while one wants to be careful, the other is unafraid of pushing forth the truth, even if it means getting into trouble with the powers that be:

Curious, gregarious, garrulous self,

did you fail to grasp the stifling norms?

To quarrel with those who rap our knuckles

for whom only their diktats

need be acknowledged,

and not what you conclude:

More than a mere issue of a poet trying to come to grasp with his inner self, Gaarriye is here telling us that even if Gaarriye as an ordinary man becomes jittery and wants to subdue truth, Gaarriye the poet will never choose the path of silence—the poet in Gaarriye will keep upholding what he knows to be true and stand by it.

The poem ‘Kudu’ is written in a folkloric style about a man-servant who had the intelligence of his king growing a pair of horns from the frontal lobe of his head like that of kudu. The man-servant was afraid to let this secret out for fear of being eliminated and the secret kept ballooning in him till he got frustrated and had to dig a hole in the earth to whisper this secret into it before burying it there. Much later and strange enough, horns kept

sprouting from the spot where this secret is buried any time soft rains touches the soil there.

Kudu is a species of horned antelope and the story is an allegory with the king representing the rulers of the country, his horns are the evil deeds he engages in, and the man-servant is the poet who cannot stomach the sight of evil and maintain silence, he must vomit his thoughts. And whenever the poet thoughts are planted, they will keep sprouting like seeds whose soil has been softened by rain water.

The implication of this poem (‘Kudu’) is that any attempt to silence the poet is worthless for truth cannot be buried. Try as much as you can, it will keep rejuvenating. Gaarriye shows us one of the fundamental employments of the African folktale in this poem. Folktales are not just stories of animals; they carry with them elements of culture and important messages in codes passed from generation to generation.

It is important to point out the similarity of style in ‘Kudu’ and the poem ‘Seer’ already discussed above. Both poems are related using the flashback technique, but whereas we hear the voice of Gaarriye aunt (Biliso) in ‘Seer’, it is the voice of Gaarriye’s father we interact with in ‘Kudu’.

It was Ben Jonson, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, who once wrote that ‘No text is innocent’ and indeed, it would be wrong for us to say he was far from the truth. Knowing the kind of despotic regime under which Gaarriye practised his art, it is understandable that he had to encapsulate his ideas in poetic diction. We have seen this in the poems titled ‘Kudu’ and ‘Seer’, and we see it again in another poem titled ‘Arrogance’. The poem ‘Arrogance’ reads like a warning to mankind to desist from being egotists and stop arrogating any inflated self of importance to human existence fornothing was created for mankind; all will continue to be even when mankind ceases to exist. The poem is most probably another hidden blow to those who deify themselves because they have managed to corner political power. He uses the poem to remind them that that the world will continue long after they are gone, that none is made to be subservient for all creatures are equal. The clue to this interpretation lies in the final stanza of this poem where Gaarriye points out that:

Of everything which is, half is secret –

however things appear

the meaning is always deeper.

Much politics shrouded the choice of the Somali language orthography before Siad Barre made a decree favouring the use of Latin letters. The pronouncement was a widely celebrated feat, and it drew the attention of poets who wrote in commemoration of that event. Even Hadraawi had written a poem titled ‘Settling the Somali Language’ in honour of that pronouncement. ‘A to Z’ is Garriye’s contribution to the archive of poems on the same subject. I think this poem was written much earlier than other poems, perhaps at a time when Siad Barre represented the salvation of the Somali race rather than its shredder to many like Gaarriye. It is also the only poem in the collection where Gaarriye eulogies the Siad Barre’s regime. This shows us that the poet is not just been petty or bitter, he knows when things are good, and says them but he never would accept silence in the face of tyranny and oppression.

‘Mandela’ is not the only poem where we get to see Gaarriye tackling suppression outside his home country. He also goes for the jugular of the United States of America’s government after she used her veto power to disallow a newly independent Angola from joining NATO. This event did notsit well with Gaarriye who employed rhetorical questions in the poem ‘Watergate’ to interrogate president Carter and lash out at the government of the United States mentioning it many atrocities, including the deaths of Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcom X, the execution of the Vietnam War, and the idea behind gifting off Palestinian land to Israelis. Gaarriye detests suppression and would reel out words against it wherever he sees it. It is perhaps this same reason which inspired his poem titled ‘Death of a Princess’.

Love hath the power to turn a cat into a lioness. We see this in the poem titled ‘Death of a Princess’. The poem is a tragic one and it is based on an actual incidence in the 1980s. It is about a Jedda princess named Misha’al who was executed for refusing the man her parent chose for her and trying to elope with her lover whom she had met while studying in the university. Her lover was made to watch her being shot before he was also beheaded. Gaarriye tells us in the poem of how the young lady defiled all else; including her family and the laws of the land she hails from; to consummate her love with her lover and thereby leading to the punishment of death for both lovers. Gaarriye points out to us that love is an uncontrollable fire for everyone is subject to its hallucinations, and he urges us never to forget the tragic event.

Typical of Gaarriye, he is that man who cannot stand oppression or suppression and denial of human rights anywhere in the world. And although the poem can be considered a love poem, ‘Death of a Princess’ reads more as a voice of protest against human rights abuse in the kingdom of Saudi.

Gaarriye love poems show an adoration of feminine beauty by showing how they either compare or contrast with natural phenomenon. In ‘Passing Cloud’, we see a poem persona comparing a girl’s beauty with the setting sun. He claims that when brought in confrontation with the girl’s beauty, the setting sun goes into hiding for the girl’s beauty surpasses that of the sun. Lastly, he recalls a fleeting moment of eye contact between them. The use of a refrain in this poem suggests the musical quality of the poem and personification makes the imagery come alive. After reading this poem, I am reminded of William Wordsworth ‘The Solitary Reaper’.

As I have observed with Gaarriye, his style of poetry is quite traditional and oral based. It is a kind of poetry that operates on a call and response system, this is why Gaarriye continues to invite fellow poets into his poems and ask them to respond to the poems. This is evident in the poem Mandela, and it can be found in the poem ‘She’ where he calls on Hadraawi (an equally prominent poet and Gaarriye’s friend) to respond to his poem.

‘She’ praises a young woman which the poet dubs Catiya. For the poet, Catiya symbolises an image of the perfect African beauty much as Leopold Sedar Senghor’s Naeet in his ‘I will Pronounce your Name’. Perhaps, the fascinating aspect of this poem are the images the poet calls up to define Catiya’s beauty. He employs rhetorical question to compare her to ‘milk’, ‘clouds giving rain’, and ‘green growth in the rainfall’. These images are important states of nature valued by the Somalis. For the Somalis, milk (gotten from their camels) is a staple food, and it is cherished by all. Also, for a people with its major populace engaged in animal husbandry, drought is detested in favour of rainfall and the greenery it comes with. These are some of the positive images he associates the young lady with. The poet also eulogises the lady’s mien and puts forward his ideals (which is probably in tandem with the Somalis) of what a perfect woman should be:

Is she beautiful, thoughtful and clever?

Does she live as she should? Does she honour

The qualities womanhood stands for?

You can see she’s not weak and not foolish;

You can see she’s not lazy and sluttish,

Not stubborn or sloppy or rowdy,

Neither a shrew nor a nag, she’s

A woman who keeps a full larder,

A woman who’d greet you and feed you.

It seems Catiya’s mien is not the only thing the poet finds fascinating, he is also enthralled by her physical beauty for he calls up beauteous images to qualify her beauty thus:

The colour of Catiya’s skin is

The colour that all women envy.

Her eyes, soft and brown, are the eyes of

The desert gazelle, while her nose is

Perfectly straight and her gums are

Black, black as charcoal. Oh, Cabdi,

The white of her teeth and the down on

Her cheek! Can you see how her waistline

Is curved like a spear; can you see how

Her arms make an elegant shape in

The air as she moves, how her calves flex,

How her neck, with its dapple of amber,

Lightly creases: the neck of a Houri.

The poet concludes that Catiya is the very image of perfection for he sees no blemish in her before calling on a fellow griot to respond to his poem:

There is nothing to fault in this woman,

Not a flaw to be found in her beauty.

…

Oh, Cabdi, you see her as I do:

A child who is almost a woman,

In the very first flush of her beauty.

I praise her. I crown her with garlands.

Haadrawi, match my song with your song.

All poems of Gaarriye bordering on love exhibit positive values connected to this theme, including ‘Death of a Princess’. However, a poem titled ‘I have Become an Apostate of Love’ seems to look into the negative aspects of love. In this poem, we meet a broken hearted persona denouncing a lover who had jilted the persona. This makes the persona turn away from love while wanting nothing to do with the lover again. He says:

Your double faced love,

Your lack of consistency,

Your conspiracy to sabotage,

Your chameleon attitude,

Will catch up with you.

If you suffer punches on the way,

Don’t turn back to me.

I am an apostate of love.

Anger, a deep sense of loss and regret runs through the tapestry of this poem and they make us empathise with the jilted persona in the poem. Aye, it is true; a broken heart never finds it easy to love anew.

© Poetry Translation Centre

Finally, Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac ‘Gaarriye’ no doubt enjoys a place of prominence among great Somali poets. His poems are powerful, filled with images, and are comparable to any standard poem anywhere in the world. The strength in his poetry lies in the employment of the oral monologue style whereby the poem is composed as if addressing another who is either present or not. His images are vivid and apt, even when his messages are veiled. Gaarriye’s poems in this collection border on either politics or love, and while his love poems are mesmerising and appealing, his political poems are harsh criticism of an oppressive regime. In Gaarriye do we see a lifelong dedication to art and his people. His is the golden voice that refuses to be encapsulated in the cocoon of silence.

Ubaji Isiaka Abubakar Eazy is a poet, short story writer, editor, book reviewer, and essayist. He holds a degree in English Language and Literary Studies and has written myriad critical essays on literature, with most published online. He currently teaches ESL/EFL at Qalam Educational and Technical Centre, Hargeisa, Somaliland.